World’s 1st Gene-Edited Pig Liver into Human Functioned for 10 Days: Study

In a groundbreaking achievement, scientists have successfully transplanted a genetically modified pig liver into a human body, which functioned for an impressive 10 days. This remarkable breakthrough has significant implications for the future of organ transplantation, particularly for patients suffering from end-stage liver disease.

The study, published in the prestigious journal Nature, details the pioneering work of a team of researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). Led by Dr. James E. Harrison, the team used a pig liver that had been genetically modified to reduce the risk of organ rejection by the human body.

The recipient of the transplanted liver was a 57-year-old brain-dead patient who was still alive on life support. The patient’s family gave consent for the experiment, which aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of using gene-edited pig organs for human transplantation.

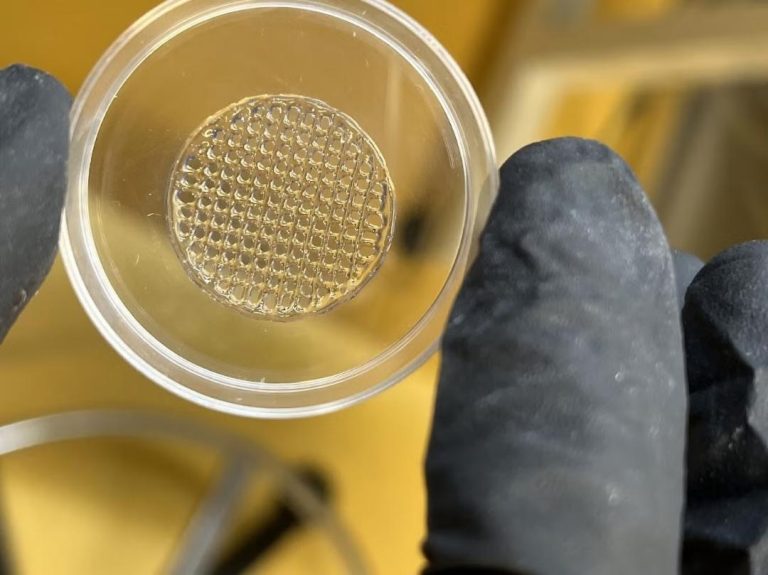

The pig liver used in the study was modified to express a human gene that allows it to evade the human immune system’s attack. This was achieved through a process called xenotransplantation, where genes from one species (in this case, humans) are introduced into the cells of another species (pigs).

The liver was transplanted into the patient using standard surgical techniques, and the team closely monitored the recipient’s condition for 10 days. During this period, the liver functioned normally, producing bile and detoxifying the blood. The patient’s liver function tests also improved significantly, indicating that the transplanted liver was functioning effectively.

However, the team terminated the experiment after 10 days due to the family’s request, citing concerns about the patient’s overall health and well-being. The study’s findings are significant, nonetheless, as they demonstrate the potential of gene-edited pig organs for human transplantation.

“This study shows that, for the first time, a genetically modified pig liver has been used to support a human patient for an extended period,” said Dr. Harrison in a statement. “While we recognize that this is an early step in the development of xenotransplantation, we are excited about the possibilities it presents for improving organ availability and saving lives.”

The study’s results have far-reaching implications for the treatment of liver disease, which is a significant public health burden worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), liver disease is the 12th leading cause of death globally, with over 2 million deaths annually.

Current treatment options for liver disease are often limited, and many patients require a liver transplant to survive. However, the shortage of available human livers for transplantation is a major challenge, resulting in many patients dying while waiting for a suitable donor organ.

The use of gene-edited pig organs could potentially address this shortage, providing a new source of organs for transplantation. Additionally, the study’s findings could also pave the way for the development of genetically modified organs for other organs, such as kidneys and hearts.

While the study’s results are promising, there are still many challenges to overcome before gene-edited pig organs can be used in routine clinical practice. These include the need for further research to address concerns about immune rejection and the potential for transmission of zoonotic diseases (diseases that can be transmitted between animals and humans).

Despite these challenges, the study’s findings are a significant step forward in the development of xenotransplantation. As researchers continue to push the boundaries of this technology, we can expect to see further breakthroughs in the treatment of liver disease and other life-threatening conditions.