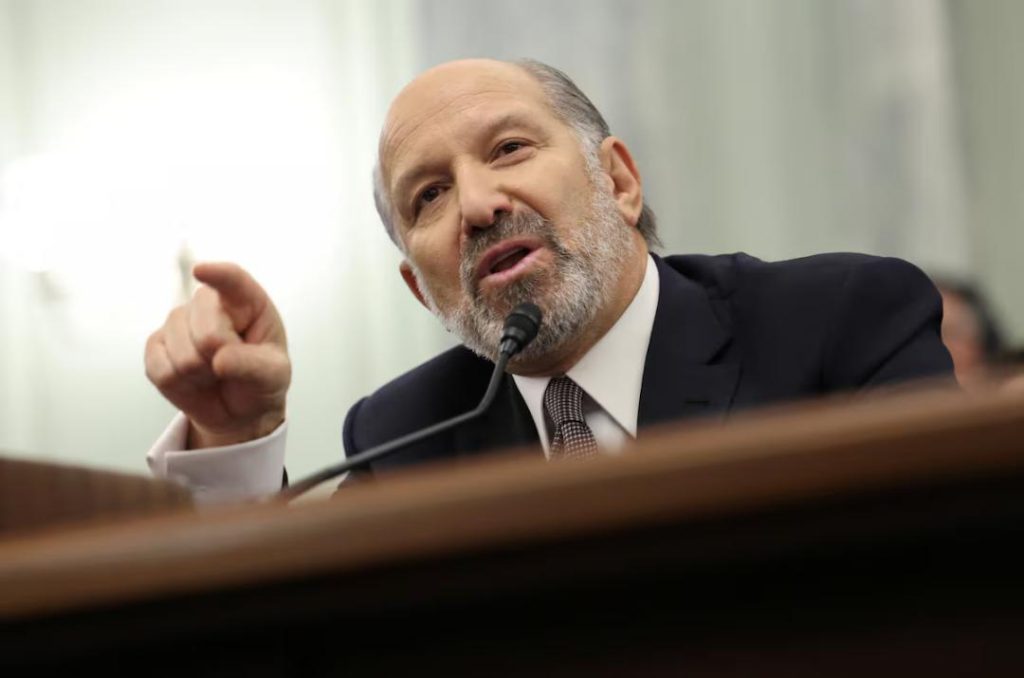

India’s Agriculture Sector Must Open Up: US Commerce Secretary

The Indian agriculture sector has long been a subject of debate, with many experts arguing that it is in dire need of reform to increase productivity and efficiency. Recently, US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick echoed these sentiments, stating that India’s agricultural sector “can’t just stay closed” and must open up to global trade. In an interview, Lutnick emphasized the need for India to adopt a more open and flexible approach to agriculture, suggesting that quotas and limits could be implemented to achieve this goal.

Lutnick’s comments come at a time when the Indian government is facing increasing pressure to reform the agricultural sector, which has been plagued by low productivity, inefficiencies, and lack of investment. The sector accounts for around 18% of India’s GDP and employs around 50% of the country’s workforce. However, despite its importance, the sector has struggled to keep pace with the demands of a rapidly growing population and the need for increased food production.

One of the main obstacles to agricultural growth in India is the lack of investment in the sector. According to a report by the World Bank, India’s agricultural sector has been characterized by low levels of investment, with public investment in agriculture declining from 5.6% of GDP in 2004-05 to 2.3% in 2017-18. This lack of investment has resulted in a lack of modernization and technology adoption in the sector, leading to low productivity and inefficiencies.

Another major challenge facing the Indian agricultural sector is the presence of trade barriers and restrictions. The sector is heavily protected by tariffs and quotas, which make it difficult for Indian farmers to compete with international producers. This has resulted in a lack of competition and innovation in the sector, leading to a reliance on traditional practices and a lack of adoption of new technologies.

Lutnick’s suggestion that India adopt quotas and limits to open up its agricultural sector is an interesting one. On the surface, it may seem counterintuitive to impose restrictions on a sector that is already heavily regulated and protected. However, Lutnick’s proposal is likely aimed at achieving a more gradual and controlled opening up of the sector, rather than a sudden and drastic shift.

Quotas and limits could be used to gradually increase the amount of agricultural produce that is allowed to be imported from other countries, while also providing a safety net for Indian farmers. For example, the government could impose a quota on the amount of certain crops that can be imported, while also providing support to Indian farmers to help them compete with international producers.

In addition to quotas and limits, Lutnick also suggested that the US is interested in doing a “macro, large-scale, and broad-based” trade agreement with India, rather than a “product-by-product” deal. This is an important distinction, as a product-by-product deal would focus on specific agricultural products, such as wheat or rice, rather than the broader agricultural sector as a whole.

A macro, large-scale, and broad-based trade agreement would involve negotiations on a range of agricultural issues, including trade barriers, subsidies, and intellectual property rights. This type of agreement would provide a framework for increasing trade and investment in the agricultural sector, while also promoting cooperation and collaboration between the US and India.

In recent years, there have been several attempts to negotiate a trade agreement between the US and India, but these efforts have been met with resistance from various stakeholders. The Indian government has been concerned about the impact of increased trade on domestic agriculture, while Indian farmers have been worried about the potential loss of markets and livelihoods.

However, the benefits of a trade agreement between the US and India would be significant. A study by the US Chamber of Commerce estimated that a trade agreement could increase US agricultural exports to India by up to $1.5 billion, while also creating thousands of new jobs in the US.

In conclusion, Lutnick’s comments on India’s agricultural sector are timely and important. The sector is in dire need of reform to increase productivity and efficiency, and opening up to global trade is a key part of this process. Quotas and limits could be used to achieve a more gradual and controlled opening up of the sector, while a macro, large-scale, and broad-based trade agreement with the US could provide a framework for increasing trade and investment in the sector.

Ultimately, the key to unlocking the potential of India’s agricultural sector is to create an environment that is conducive to investment, innovation, and competition. This will require a combination of policy reforms, investment in infrastructure and technology, and a willingness to open up to global trade. By working together to achieve these goals, India and the US can promote economic growth, create new opportunities, and improve the lives of millions of people.